![]()

If you read nothing else, read this…

- Employers require accurate and meaningful data to be able to assess the impact of their health benefits.

- Benefits and HR professionals require analytical skillsets to be able to assess their findings.

- But it is often difficult to show a correlation between the implementation of a health benefit and a healthy workforce.

But the impact of employers’ efforts, even in organisations where healthcare benefits are well established, remains to be seen.

Kirsten Samuel, founder of health and wellbeing consultancy Kamwell, says: “Big employers are running all these wellbeing initiatives, but if you were to ask them what the impact has been at the end of the year, [they would struggle to provide] hard data.”

But this does not mean that the task is impossible.

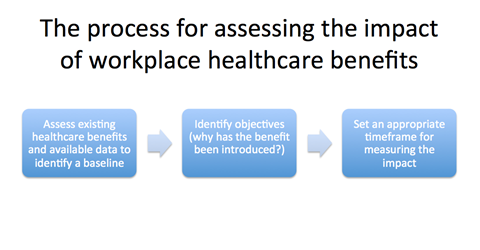

Employers that want to track the impact of their health benefits should start by assessing the perks that that they already have in place and the data that these provide, if any.

“This will provide an organisation with an indication of the type of data that is already available to it and provide it with a baseline, so that it can then pinpoint the areas of its business that need the most improvement,” Samuel adds.

For example, an organisation may have one business division with a particularly high sickness absence rate that needs addressing.

Rich data sources

Employee absence records, staff engagement surveys and reports generated from health benefits, such as private medical insurance (PMI) and employee assistance programmes (EAPs), can provide rich sources of workforce health data that an organisation can use by way of a baseline.

Employers may also use data sourced from workplace health risk assessments, health screening, wellbeing portals and wearable technology.

Employers should then identify their objectives, which should involve reviewing why they implemented their healthcare benefits in the first place.

Typical employer objectives include a desire to reduce sickness absence or to boost employee engagement. Objectives may also be preventative, as in the case of a health screening campaign designed to, say, detect heart attack risk in female employees, as is the case with Danone (see case study, below).

An objective is key, because it constitutes the measure by which an employer can attempt to assess the impact of its health benefits.

Finally, an employer should identify a timeframe for assessing the impact of a benefit. For example, an employer may introduce a stress management programme to help tackle high sickness absence rates, which may involve measuring its sickness absence rate both before and then over a set period, such as a year, after implementing the programme to measure its effectiveness. Employers should decide on the timeframe they will use at the outset because, in some cases, 12 to 18 months may be a more appropriate timeframe.

But there will, of course, always be some employers that have implemented a health benefit as a ‘nice to have’ or because their competitors offer it, without any underlying objectives. But considering the long-term relevance of offering such perks in their organisation could stand these employers in good stead.

Benefits of impact tracking

Employers that track the impact of their health benefits can more easily pinpoint specific health issues and affected staff, which can help to boost employee health and wellbeing and, therefore, engagement. This tailored approach to health benefits management enables employers to make often substantial cost savings by avoiding offering health benefit support to staff who do not need it.

But there are a number of challenges that employers could face along the way.

First, there is the difficulty involved in data collection, ranging from the effort of sourcing benefits data from healthcare providers to the challenge of sourcing relevant data from internal departments across an organisation, and often multiple members of staff.

Beate O’Neil, head of wellness consulting at Punter Southall Health and Protection Consulting, says: “Quite often, different sections of HR are in charge of different benefits, so [employers] may find [their] PMI reports coming into [their] head of HR and then EAP reports coming in to someone else, and that might not be the employee who deals with absence and occupational health.”

Employers must also ensure that their data is fit for purpose. This does not just mean ensuring its accuracy, but also that it relates to relevant populations, or sufficient numbers, of staff. Some benefits, such as PMI, for example, may only be offered to senior staff, which means that an employer’s data sample may be relatively small. This may then mean that they cannot draw meaningful conclusions, or spot useful trends with which to help shape their health strategy.

Finally, organisations must assess whether or not their employees have the time and the necessary skillsets to analyse data in-house.

Oliver Gray, founder of health consultancy EnergiseYou, says: “HR has a hell of a lot on its plate, and taking that first step of [designing] a proactive wellbeing programme is a job in itself. Also, it’s quite an analytical thing to do, and HR does not tend to be that analytical.”

But perhaps the greatest challenge is the fact that employers cannot force staff to take up the health benefits that they implement, and even when staff do there is no guarantee that they will stay with an organisation to enable it to track the effectiveness of any benefit or intervention to which they have been party.

It is also often extremely difficult for an employer to prove any correlation between the implementation of a health benefit and a healthy workforce. Kamwell’s Samuel says: “Employers are trying to define proper metrics and measures, but undoubtedly it will be tricky in some areas, and there are certain things that are easier to measure than others.”

But employers should not stop trying to do so, because the value of the exercise is worth its weight in gold. As Alex Higman, operations director at Bluecrest Health Screening, says: “Intrinsically, employers know that healthy employees are happier, more engaged and more productive.”

Encouragingly, a number of organisations are already on the right path. “Many employers are now at the point that they want to learn from their experiences. [They know that] in order to make improvements on future decisions and interventions, they need to know whether or not the initiatives that they have run previously have been successful, and the only way to do that is to track what they are doing over a period of time,” says Samuel.

Case study: Danone tracks health assessment impact to help support staff needs

Danone has been able to tailor its healthcare strategy to support employees’ needs by tracking the impact of the employer-funded health assessments that it rolled out to all staff last year.

As a result, 476 staff undertook a health assessment between the launch of the benefit last April and the end of the year.

John Mayor, head of UK rewards and HR project management at Danone, says: “Within the data set, we have very a robust set of management information, so we have the opportunity to drill down and look at key trends within our businesses.”

The organisation can now, for example, more easily identify staff who need support with, say, smoking cessation or healthy eating.

Danone appointed health screening provider Bluecrest Health Screening to deliver the health assessments to staff, along with bespoke reports detailing key measures such as body mass, heart rate, lung capacity and cholesterol.

The organisation, which won the award for ‘Most engaging benefits package’ at the Employee Benefits Awards 2014, has tailored the assessment in line with its healthy digestion-focused yogurt product ranges Activia and Actimel.

Mayor says: “We are very concerned about vitamin D and celiac disease [a digestive disease that damages the small intestine], and these have been added into the screening at no extra cost.”

Danone will also introduce more stringent testing for heart attack risk for its female population this year.

The organisation funded expanded staff access to the health benefit by reallocating £100,000 worth of savings that it made by discontinuing the dependents’ death-in-service pension it previously provided to staff in one of its business units.

Viewpoint: Beware of taking wellness initiatives to extremes

Employers have traditionally relied on offering higher pay packets and better perks. But now, many potential recruits claim they would rather trade off a higher wage for a better work-life balance. As a result, organisations have started to rethink the way they reward people. Instead of relying on monetary incentives, they have started to try to offer more attractive workplaces. This takes many forms, from nice working environments to flexible work arrangements and better facilities. But one trend that has caught on recently is trying to improve employee wellness.

The idea behind the corporate wellness movement is that organisations can help to improve their employees’ wellbeing at work. They try to do this by offering everything from cut-price gym memberships and weight-loss programmes to in-house mindfulness classes and healthy-eating initiatives. Some employers that have taken this to an extreme have started to install treadmill desks and institute walking meetings. A number of US healthcare organisations have placed a ban on employing smokers. One organisation in Sweden even requires its employees to attend the gym twice a week if they are to receive their entire salary.

In small doses, corporate wellness programmes can do a little good. Employees appreciate free gym membership, and at times they find it helpful when employers offer health improvement initiatives. However, we should not think these wellness initiatives are going to be a magic bullet.

A study of wellness initiatives in US organisations suggests they tend to be costly, but have fairly limited impact on employee health. For instance, the small number of employees who participated in weight-loss programmes lost on average only 1kg. There is a danger that when they are taken to extremes, wellness initiatives can backfire. They can be experienced by employees as an unhelpful interference into their personal lives. In some cases, they can stoke a sense of anxiety and insecurity. At the extreme, they can mean employees spend more time working on their own personal wellness rather than their work tasks.

Andre Spicer is Professor of Organisational Behaviour at Cass Business School

Source: Employee Benefits