If you read nothing else, read this…

- Evidence shows that the greater the choice of pension funds, the less engaged employees may become in the scheme.

- Some employees in some market sectors, such as financial services, will always be more engaged than others.

- Many employers just want to get through auto-enrolment and not consider fund choice.

The Pensions Regulator’s (TPR) principles for investment governance of work-based DC pension schemes require employers to look at the number of investment funds they offer their employees, and to consider how the number of funds on offer might affect scheme members’ ability to make effective investment decisions.

TPR also requires employers to offer an adequate range of investment options that reflects the expected risk tolerances and requirements of scheme members, including the likely format and structure of their retirement benefits, and consider how these options may change as members approach retirement.

But employers face a number of challenges in meeting these requirements.

Firstly, the definition of ‘adequate’ is anyone’s guess, as is the appropriate number of funds employers should offer their employees. Then there is anecdotal evidence that many employees remain uninterested and unengaged in their employer’s pension scheme despite the introduction of auto-enrolment in October 2012, let alone making strategic fund and investment decisions. For sure, benefits and pensions professionals will have their work cut out on pensions for the foreseeable future.

Strategic decisions

Whether employees are actually capable of making such strategic decisions remains to be seen. According to the Office of Fair Trading’s Defined contribution workplace pensions market study , published in September 2013, a number of research studies on behavioural economics have raised serious doubts about employees’ ability to make strategic investment decisions and informed choices between investment funds.

Andrew Cheseldine, a partner at actuarial consultancy firm Lane, Clark and Peacock, says employers should limit the choice of funds they offer their employees.

Speaking at the National Association of Pension Funds’ annual conference and exhibition 2013 in October, he said employers that offered staff too much fund choice actually dissuaded them from investing.

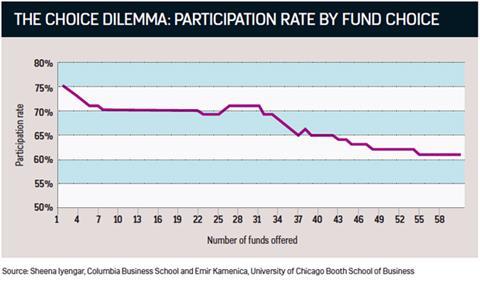

He cited research entitled Choice proliferation, simplicity seeking and asset allocation , by Sheena S Iyengar, professor of business at Columbia Business School and Emir Kamenica, professor of economics at the University of Chicago Booth School of Business, published in April 2010, which found that offering just one fund resulted in 75% of employees joining a scheme, whereas offering 58 funds resulted in just 62% joining. The research was based on the US pension scheme, 401k.

“By definition, [employers] can see that the more funds they have, the fewer [employees] actually join the pension scheme,” Cheseldine says. “That’s about as adverse a reaction as they can get.”

Darren Philp, head of policy at pensions provider B&CE, says: “What we’ve tried to do is just make it very simple, so we offer, broadly speaking, six fund choices.

“What we didn’t want to do is overwhelm employees with complexity and choice because I think I would agree with the view that if employers bewilder staff with choice, they are less likely to engage.

“Auto-enrolment is all about harnessing inertia, so employers are trying to get employees saving without them having to make big decisions.”

Philp says employers should focus on ensuring their default fund is fit for purpose, rather than on fund choice, in view of the probability that most employees will select the default fund.

“If you overwhelm people with choice and over-complicate things, they are likely to switch off because they just haven’t got the information or capacity to make that decision,” he adds.

Britt Hoffmann, head of UK defined contribution (DC) at pensions adviser P-Solve, says: “From our experience, it is quite clear that most employees rely on either their trustees or their employer to get it right for them.”

Hoffmann points out that most employers tend to have a minority of staff who are relatively active investors. But active does not necessarily mean competent, she warns.

“There is a group of employees, typically 5% of a membership, that tends to be more active, but we find they are making choices that look quite strange: either making investment choices too late or making [asset allocation] switches at the wrong time, and we think a lot of that is down to the fact that while they might be financially literate, they are not necessarily investment literate,” she says.

But this is not the case for employees in all market sectors. For example, many staff working in the financial services market are likely to be better educated about their organisation’s pension scheme and fund offering because of their professional skillsets.

These employees may also be more likely to manage their pension investments regularly. But this is not the norm for most pension scheme members.

Hoffmann adds: “We went into auto-enrolment expecting to give employees choice, and for them to make their own investment decisions, and technology allows for immediate [asset] switching.

“Clearly, there is this general perception that employees need instant access to things that can instantly change, but, in reality, when we track how much activity there is in terms of logging on and making fund choices, there’s very little. I think this will change, but the focus for employers so far has been on ticking the auto-enrolment box and getting something in place.”

B&CE’s Philp says: “The vast majority of employers just want to get through auto-enrolment . They want their employees to be auto-enrolled into a pension and they want their employees to have a degree of choice, but ultimately it’s the [retirement fund] outcome that they’re really interested in.”

He adds that employers’ responsibility is to offer their workforce a suitable suite of funds and allow employees to have some limited ability to self-select their investment funds. “It’s then up to the trustees to assess their workforce and decide what the optimum number of funds is,” he says. “There’s no magic answer to that.”

Case study: Marriott Hotels keeps funds in check

Marriott Hotels auto-enrolled its 8,000 full-time employees in early 2013.

Its staging date was April 2013, but it postponed auto-enrolling its workforce until 1 July 2013 with the help of its adviser, Berkeley Burke, which also manages the organisation’s private medical insurance and group life assurance .

Sarah Newsome, manager, employment law/compensation and benefits, Marriott Europe at Marriott Hotels, says: “Fund choice was a factor. It wasn’t the most significant factor, but it was certainly a factor because we didn’t want a provider that had hundreds of different funds. We wanted to make sure there was an array of funds, but not just this mass of them that caused confusion.

“Anyone I know who is involved in pensions in any way says there is so much choice, and unless you’re an absolute expert, it really is very difficult for them to make that choice. I would imagine many employees just opt for the default automatically because they just don’t know where to start looking when there’s a huge array of choice.”

Marriott first considered eight pension providers for auto-enrolment, then whittled these down to three before choosing B&CE. Newsome says: “It was the fact that there were six funds. It’s a much more limited selection, which I think is an advantage to our employees.”

Newsome and her team have created a comprehensive communications strategy to underpin Marriott’s auto-enrolment programme.

Before its staging date, this involved Newsome presenting webinars for hotel-based general managers and leadership teams. She then sent bespoke presentations for them to deliver at town hall meetings, detailing what the regulations meant and how they affected employees.

Each employee also received a personalised letter from Marriott Hotels and B&CE explaining the ramifications of auto-enrolment and what to expect.

Berkeley Burke also spelt out the organisation’s strategy at each of the group’s 55 hotels.

The results speak for themselves: Marriott’s opt-out rate is about 7%.

Newsome advises fellow employers to consider the demographics of their workforce before deciding on their fund range. “We have a very mixed demographic as a hotel company, so we really wanted to go for a simpler approach and make it easier for our whole population to understand [our proposition], but still give choice for those who wanted it,” she says.