We have all experienced that moment where we sit back and think, “Why did I buy this?” It doesn’t matter what “it” is or in what form this question appears. We’re all familiar with it.

We have all experienced that moment where we sit back and think, “Why did I buy this?” It doesn’t matter what “it” is or in what form this question appears. We’re all familiar with it.

Other questions we might ask, are “Why did I buy this, and not that?” “Why did I choose and pay for this service when its competitor clearly offers a better deal?” “Why didn’t I realise this when I signed up?”

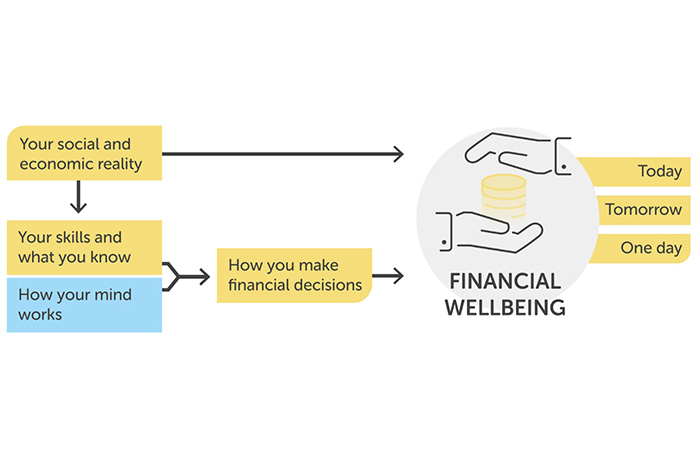

Financial wellbeing refers to our state of competency and levels of resulting happiness when it comes to the utilisation of our finances.

A healthy state of financial wellbeing means being able to provide for our financial needs of today, whilst able to save for those aspirational goals of tomorrow and having sufficient funds for when we one day ultimately stop working. 4me, our digital benefits platform, helps employees take control of their financial needs so they can make a positive difference to their lives.

What influences our financial wellbeing?

To some extent our financial wellbeing is determined by our individual social and economic realities and these are more difficult to change or impact. But what also determines our financial wellbeing, and which we CAN influence directly, is how we make financial decisions.

To some extent our financial wellbeing is determined by our individual social and economic realities and these are more difficult to change or impact. But what also determines our financial wellbeing, and which we CAN influence directly, is how we make financial decisions.

In turn, our decisions are shaped not only by what we know – our knowledge of what to do with our finances – but also by how our mind works. It is in this area that we often spend too little time.

How does our mind affect financial wellbeing?

We have logical contributors to making a decision and also those that are emotional by nature. Both are cognitive. The logical ones are easier to manipulate and influence, to change or amend, but the emotional ones less so.

When we become aware of what these contributors are and how they work, we arm ourselves with a very important tool that will have an almost immediate effect on our financial wellbeing.

We often don’t realise the extent to which our brains take mental shortcuts on the way to making a decision. These shortcuts, called heuristics, are mostly good and helpful, but they can also work against us making the correct decision for our circumstances.

For example, say you receive an unexpected windfall of £1,000. Some of us will simply spend this money on something we don’t normally include in our planning, or cannot normally include because of budget constraints or another reason. Easy come, easy go, is how we’d describe this. Our minds put the £1,000 in a little box defined by its source.

This is similar to the way our brains would allocate a portion of our salary toward paying the mortgage, or the rent. In other words, we define what the funds are for (rather than by where they are from). In truth, the source of our funds shouldn’t have such a deterministic impact on what we spend it on.

Thinking differently to improve financial wellbeing

Sometimes all it takes is to take a little more time over our available options before making a decision. Having the knowledge to recognise WHEN we take these shortcuts to an intuitive decision and then to develop the ability to stop that process and have a good think over what we do, will give us a fighting chance to make better financial decisions.

In Thinking, Fast and Slow, Daniel Kahneman’s best-selling book on the subject of the psychology of decision-making, he speaks of two modes of thought. He calls it “System 1 – fast and intuitive” and “System 2 – slower, more logical”.

In this context, the behavioural biases described above would be examples of System 1. We can allow this mode of thinking, which is our default, to run its course OR we can purposefully switch to System 2 in order to ensure we consider our options from all angles.

When we make decisions we are prone to committing mental errors purely as a result of what is known in the academic world as behavioural biases. This occurs when we naturally give more weight to a certain aspect of the information we’re presented with than the other aspects of that information, for no substantive reason.

What does this mean for me, in practice?

When you’re faced with a financial decision, be aware of what might trip you up or trick you mentally into choosing a less than optimal path.

Some of us prefer well known paths to new ones. Some of us look for information confirming what we already think we know rather than consider information that would challenge our way of thinking. This is all human nature.

The framing effect

Take the well-known bias called the FRAMING EFFECT, for example. All of us respond more or less favourably to information depending on how it is framed. There are often more than one way to define (or to frame) the exact same thing and marketers make use of this in a very clever way by tailoring it to the consumer group they are targeting.

Our brains manage to recall a painful memory from a loss easier than it does a joyful memory from a past gain. We therefore react in a certain emotional way when a message is framed in a negative way and, for this reason, these types of commercial messages are very effective. Take, for example, the health warnings on cigarette packaging. They’re far more effective than highlighting the health benefits from NOT smoking.

Which of the following messages about retirement would resonate with you more?

- Unless you increase your pension contributions you’re going to fall short and not be able to sustain the lifestyle you’re accustomed to.

- By increasing your pension contributions you will be able to sustain the lifestyle you’re accustomed to.

They’re both saying the same thing but each will have a different rate of success (the reader increasing their pension contributions), depending on whether the reader leans toward responding to negative or to positive framing.

You might miss a fantastic financial opportunity or make an incorrect financial decision simply because you don’t recognise a certain message or a piece of information as being valuable.

So make it a goal to understand your unique decision-making biases in order to improve your financial wellbeing. Make it your goal to understand your answer, next time you ask: “Why did I buy this?”