Corporate investors are recognising the value of information about the health and wellbeing of employees, but disclosure by employers has been slow to develop

If you read nothing else, read this …

- Most FTSE companies disclose information about the health and wellbeing of their employees.

- But disclosures tend to be inconsistent across organisations in terms of volume, content and format.

- Greater disclosures about workplace health can help investors understand any potential risks to organisations in which they are buying shares

When almost £1 billion was wiped off Lloyds Banking Group’s share price last November when chief executive António Horta-Osório went on sick leave with stress and fatigue, many other employers were left wondering whether greater disclosure about employees’ health and wellbeing was really in their best interest.

The drive for greater disclosure about employees has been going on for decades. But workforce health has never been a main topic for discussion, despite spiralling sickness absence costs and the impact on employers’ business performance and, therefore, profitability.

However, a government report, Accounting for people, published in 2003 (see box below), which recommended greater reporting on human capital management (HCM), managed to fuel interest from the corporate investment community before being shelved. These interested parties are now pushing a new initiative for disclosure of HCM information and, for the fi rst time, data on workforce health.

Proactive approach to health

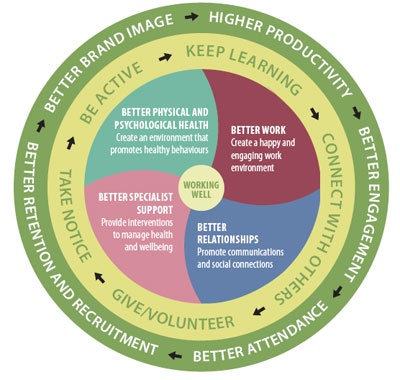

The initiative is the brainchild of UK charity Business in the Community (BITC), whose Workwell campaign aims to force employee wellness and engagement onto board agendas, and to encourage a more proactive approach to employees’ physical, psychological and social health.

BITC views staff as a critical business asset, and takes issue with the fact that so many employers currently fail to show how they are managing this asset effectively.

It also highlights a lack of consistency and quality of what is being reported.

Understanding how employers manage their workforces can give potential investors useful insights into risks and opportunities, according to the charity.

Robin Roslender, chair in accounting and finance at the University of Dundee’s school of business, has written extensively on the merits of employers disclosing information about the health and wellbeing of their staff . A paper co-authored by Roslender, entitled Towards recognising workforce health as a constituent of intellectual capital: insights from a survey of UK accounting and finance directors, says a workforce showing high levels of health and wellbeing, underpinned by significant health awareness, which in turn translates into healthy lifestyles, promises to create and deliver value more successfully than one which exhibits lower levels of health and wellbeing.

Good health profile

The paper also says that an organisation with the infrastructure in place to support a good staff health profile will be more likely to succeed than one that has adopted a more passive approach to workforce health.

Sue Connelly, global health and wellbeing lead at pharmaceutical company AstraZeneca, says her team realised long ago the value of disclosing information about employee health, which is why she has been formulating a strategy. “Instead of looking at things that perhaps are a bit obvious, you can look at your employee opinion survey and see what people are talking about, such as whether they think there are adequate safety measures in the areas where they work,” she says. “We report that through to investors and make interventions depending on what that information is telling us. We also report accidents and illnesses through our global reporting system.”

AstraZeneca (see below) tracks eight to 10 illnesses across the business, including any contracted by staff travelling on company business. It also tracks cases of work-related stress and

discloses its findings in its annual report and accounts.

It is one of a number of employers, including Anglo American (see box below), BT Group and Nationwide Building Society, that disclose information about workforce health. But it may be some time before this trend develops further.

Lack of genuine regard

Roslender thinks a general lack of genuine regard by UK employers for their staff is a major obstacle to health disclosures. In a study cited in his abovementioned report, a poll among accounting and finance professionals in 1,000 UK organisations showed respondents thought their employers viewed workforce health as reasonably important, but probably not a critical concern. “In the UK, the idea that people are the most valuable assets is pretty well bollocks,” he says. “It’s not even rhetoric. In the UK, labour is just a commodity to be exploited.”

Roslender says there is also a reluctance in the audit profession to account for people because of the additional work involved, but he acknowledges the potential difficulties. “The idea of accounting for people would be to put them on the balance sheet, and in some sense you would have to give them a value,” he says.

“We have enough problems with intangible assets like brands and corporate reputation and, to some extent still, general goodwill.”

But Nigel Sleigh-Johnson, head of the financial reporting faculty at the Institute of Chartered Accountants in England and Wales, believes the slow evolution of disclosures is more due to a lack of demand for information on workforce health. “There is already a requirement for companies, except small ones, to report in their business review on important employee matters, although not health and wellbeing particularly. But I think that is where you get into a level of prescription, and I think there is a consensus on this in the UK that this really isn’t very helpful.”

View of investors

This seems to be the view of investors in mining group Anglo American, which prefer to receive information on employee safety.

Frank Fox, head of occupational health at the mining group, attributes this to the extent to which the mining industry is high risk and, therefore, constantly under scrutiny by investors and stakeholders.

Ben Willmott, head of public policy at the Chartered Institute of Personnel and Development, is not surprised by this finding, and says information on workforce health is typically more in demand from investors in high-risk industries, such as oil and gas, and mining, as in the case of Anglo American.

Nevertheless, Willmott says more needs to be done to educate investors about why workplace health disclosures are important.

“Do investors really understand the link between higher levels of stress, accident levels and lost productivity?”

Pensions and Investment Research Consultants (PIRC), which advises institutional investors on corporate governance and corporate social responsibility, has long been interested in greater employer disclosure about their workforces.

Jim O’Loughlin, a consultant for PIRC, says it has been looking at what, besides remuneration, drives employees to go to work and perform. “A lot of the factors it believes are important are non-financial in nature, such as sense of purpose and autonomy at work,” he says. “If we delve deeper into these things, a lot of them do have health-related benefits.”

Lack of understanding between HR and finance

Some lack of understanding between HR and finance departments on workplace health is another obstacle to greater disclosure. Employee health and wellbeing tends to be seen as an HR concern, despite its effect on an organisation’s bottom line in terms of sickness absence, for example, and therefore does not often appear on boardroom agendas.

So where should employers that want to provide greater disclosure about their workplace health start?

Patrick Watt, director of corporate in Bupa’s sales and marketing team, suggests starting with disclosures about the products and services the employer provides to help its employees remain healthy, rather than the conditions they may be suffering from, such as mental health problems, which remain stigmatised. “Where employers can really diff erentiate themselves is by disclosing what they do to support employees, which I think is much more relevant to investors,” says Watt. “I think it is much more powerful to say ‘we recognise the health and wellbeing of our employees, it is hugely important to us and, as a consequence, we are investing in providing this support for them’.”

Public reporting guidelines

BITC’s public reporting guidelines are the most comprehensive framework currently available for reporting on workforce health (see box above). BITC is now in the process of tracking FTSE 100 companies’ adherence to these guidelines.

Until disclosure levels are agreed, the vehicle in which they are made remains academic. Nevertheless, Sleigh-Johnson advises employers to consider the fact that the information that is measured and reported internally within a business is not necessarily the same as the information that is, and should be, reported in its annual reports and accounts.

“One has to look at why one wants particular information to be disclosed,” he says. “If it is to achieve social policy objectives, which I think there was a flavour of in the Accounting for people report, then there has to be a judgement about what is the best place to make that sort of disclosure, whether it is the annual report or elsewhere.”

The backdrop to such considerations is a global debate on integrated company reporting. Sleigh-Johnson explains: “It is not looking at individual strands [such as workplace health], it is looking at how all the existing individual strands can be bought together in a more cohesive and succinct way to provide an integrated report that can satisfy the needs of the various users of a company’s reported information.

“The thinking is that the annual report is there principally to serve the investors, but there other types of information that are important, other users of reported information, and there is a feeling that there needs to be some way [to include this].”

CASE STUDY

Anglo-American mines essential employee safety data

Mining group Anglo American discloses information about its employees’ health and wellbeing because it believes it is important for stakeholders to know what the organisation is doing.

But Frank Fox, head of occupational health at the organisation, concedes that investors are currently more interested in employee health in the context of safety than of wellbeing, particularly the Global Reporting Index (GRI), which is a global sustainability reporting framework run by the Global Reporting Initiative. “[GRI] asks for safety information,” he says. “It is starting to ask more for health, but it is more occupational health.”

Fox points out that greater disclosure is not necessarily positive if the metrics are wrong. “There is a certain amount of information that is requested around absenteeism, which is what many people think of as an index of health,” he says. “Personally, I don’t think so. I think it is more an index of dissatisfaction with the organisation. Absenteeism is a very nice measure, but it is not necessarily around sickness.”

Anglo American’s global operations run a range of health programmes, which have certain deliverables measured against internal standards. Results data is reported into a central group database, which is used as the basis for the organisation’s reporting.

All data is audited externally where possible. Fox adds: “So, if we say we vaccinated 100% of our workforce against flu last year, then we can actually prove that, and where we have our HIV/Aids programmes in southern Africa, if we say we have achieved certain things, the data that comes out of those programmes is audited.”

But by his own admission, Fox says his approach to deciding the type and level of information disclosed is a movable feast. “We try to report on what we do and the measures of our success and, to some extent, the measures of our failures because we believe in being transparent,” he says. “But because it is [the information] not being asked for, it is rather diffi cult to gauge what one should report and what is necessary.”

Fox says investor feedback and bodies such as UK charity Business in the Community help to inform his decision-making process, as do the respective reporting practices of the company’s industry peers.

CASE STUDY

AstraZeneca finds the right medicine

AstraZeneca has been developing its health and wellbeing reporting strategy in recent years because it wants to show investors the support it gives employees to remain healthy. The disclosures also help the organisation maximise its score on the Dow Jones Sustainability Index, a benchmark for investors that integrate sustainability considerations into their portfolios.

Sue Connelly, global health and wellbeing lead at AstraZeneca, says: “We took the proactive elements of health and wellbeing away from occupational health in 2008/9 and moved it into HR to align with engagement and productivity. Occupational health can often be seen as reactive, making sure people are not exposed to harmful elements in the workplace, whereas what we are doing is more proactive.”

There are three pillars to the health and wellbeing strategy the firm introduced last year: personal energy management, health screening, and a set of six essential health activities: physical fitness, healthy business travel, workplace pressure management, tobacco use cessation, healthy eating and general health promotion.

AstraZeneca aims to have the six activities in place in more than 80% of its 60 global sites by 2015. Tools, such as workshops and access to fitness activities, are in place to help each site achieve this and results are monitored via an internal tracking system.

Connelly says: “We review progress on an annual basis and do a gap analysis, and we support areas around the globe that are not quite meeting that target to ensure that, by 2015, they have all six. We have a glidepath, so in year one we wanted one of the core activities to be in place; this year we want two in place, and so on.”

Each locality decides which activity it wants to introduce and when, as long as it meets the long-term objective by 2015.

Connelly says there are many benefi ts in formalising a health and wellbeing strategy, one of which is a better relationship with the organisation’s finance team.

“We have looked at the scientific evidence for introducing certain aspects of the health and wellbeing strategy and have put those into place,” she says. “Reporting on it enables employees and managers and marketing companies [to understand] what health and wellbeing means for us and how we are meeting our targets.”

BUSINESS IN THE COMMUNITY REPORTING GUIDELINES

Published in May 2011, the guidelines are based on four principles:

- Demonstrating a robust employee wellness and engagement strategy linked to securing business objectives, ensuring a strategic approach to skills and talent that meets current and future business needs.

- Ensuring employee communication and voice supports engagement.

- Taking a proactive approach to building physical and psychological resilience to support sustainable performance.

- Providing a safe and pleasant environment that supports wellness and productivity.

- BITC is now tracking FTSE 100 companies’ adherence to these guidelines.

A BRIEF HISTORY OF HEALTH AND WELLBEING

- Two notable eff orts to devise a people reporting system in recent decades are the Skandia Navigator and the balanced scorecard. These focus on employees’ working environment and competencies rather than health and wellbeing.

- Skandia’s model was designed to measure finance, as well as intangible assets such as customers, internal processes, renewal and development (sustainability) and employees.

- The balanced scorecard (a result of a study led by accountancy firm KPMG’s research arm, the Nolan Norton Institute, in the 1990s) was based on four principles: learning and growth perspective, internal perspective, customer perspective and financial perspective.

- More recent eff orts came in 2003, when the Department for Trade and Industry (now the Department for Business, Innovation and Skills) initiated its own research. Its taskforce produced a report, Accounting for people, in November 2003.

- The report concluded that reporting on human capital management (HCM), defined as a strategic approach to people management focusing on issues critical to an organisation’s success, is relevant to institutional investors because they take a greater interest in the sustainability of companies they help to fund.

- The report recommended that information about HCM should be included in employers’ operating and fi nancial reviews, which have since been replaced by business reviews, with a view to these disclosures becoming mandatory.

- This recommendation was withdrawn by the then chancellor, Gordon Brown, leaving businesses no closer to any sort of equilibrium for people reporting, let alone any disclosures around workforce health.

time [url=http://www.forkshoes.com/christian-louboutin-wedge-espadrille-255-lady.html]wedge Espadrille[/url] wedge Espadrille ? [url=http://www.forkshoes.com/christian-louboutin-altadama-peep-toe-pumps-15225-lady.html]altadama peep-toe pumps[/url] altadama peep-toe pumps [url=http://www.forkshoes.com]christian louboutin outlet[/url] christian louboutin outlet [url=http://www.lingeriesroom.com/sexy-one-piece-swimwear-teddy-h2157-white-h2157-good.html]discount sexy swimwear[/url]honored?tradition I? [url=http://www.forkshoes.com/short-boots.html]short boots[/url] short boots [url=http://www.forkshoes.com/christian-louboutin-square-heel-tall-boots-black-406-lady.html]square heel tall boots black[/url] square heel tall boots black have? [url=http://www.forkshoes.com/christian-louboutin-slingback-pump-black-65245-lady.html]slingback pump black[/url] slingback pump black a couple of ideas and printables. [url=http://www.forkshoes.com/christian-louboutin-net-seude-pumps-429-lady.html]net seude pumps[/url] net seude pumps The ideal breakfast tray genuinely is about the styling. Just before putting any goods around the tray look for a very fabric or leftover wrapping paper to line the within and tie some coordinatign ribbon for the handles. Location a pre-brewed cup of tea of espresso from the corner with our printable sugar sachet tucked to the saucer [url=http://overvintage.com]junior bridesmaid dresses[/url] junior bridesmaid dresses [url=http://www.forkshoes.com/christian-louboutin-margi-diams-120-sandals-540-lady.html]margi diams 120 sandals[/url] margi diams 120 sandals . Put your picked breakfast food inside the centre plus the serviette and cutlery (wrapped within our printable band) along with. End from the tray having a tiny vase showcasing a number of blooms from the preferred bouquet. By doing this she ll reach take pleasure in her flowers in the course of breakfast before?finding?the best

natural vigora sildenafil citrate

sildenafil citrate cia